One dark, cold winter night in early 1986, ten clergymen gathered in Winchester Square for a meeting whose outcome would ultimately send shockwaves of controversy throughout the political scene in Springfield. As the ten men of the cloth met that night in the heart of Springfield's black community, they reflected on the state of the Winchester Square neighborhood which comprised the membership of their respective churches. They described a community ruined by blight, poverty, crime with non-existent economic development. Yet they knew that large sums of public money, in fact tens of millions of dollars, had been spent by the government supposedly on economic development in Winchester Square.

The clergy found themselves using terms like, "the aftermath of an atomic blast," "Berlin, 1945" and "a wasteland" to describe what had become of their neighborhood. What happened, they wondered, to all the millions of dollars (90 million in all since 1966) that had been poured into Winchester Square? Why was there so little to show for it? Bowing their heads in prayer, the religious leaders of the black community joined together that night to make a solemn vow - forming a covenant - that they would wage a fight, no matter how difficult, no matter where it led, to find out what had become of all the government money that had been intended for Springfield's poorest neighborhood.

Councilor Morris Jones, the only black member of the City Council, was the first to make news of the existence of the Covenant known to members of the City Council. Jones approached Mitch Ogulewicz and Francis Keough and asked them to meet with the group. At that meeting, the clergy told Ogulewicz and Keough, using colorfully blunt language, that they were demanding that an audit be conducted: a line by line, dollar by dollar examination of where all of the money that had been allocated to Winchester Square from government economic development programs had actually been spent going back to 1966. Ogulewicz agreed that the requests of the clergymen were reasonable, and promised he would take their proposal for a complete financial reckoning back to the other Councilors.

However, before any plans could get off the ground, the Mayor caught wind of it. Richard Neal immediately announced that he was adamantly opposed to any such audit. Neal dismissed the audit as "a fishing expedition" and said that with an estimated price tag of $250,000, it was too expensive. However, some in the Covenant suspected that there were other reasons for resistance to the audit, reasons that perhaps were only discussed within insider circles.

The audit the Covenant requested would've covered some very sensitive programs in Springfield, such as Model Cities, a disastrous early economic development program that demolished the housing in poor neighborhoods even when they didn't have anything to put up in their place. The audit would also have covered the CETA program (Comprehensive Educational Training Act) a job training program that was so scandal plagued and unsuccessful that Congress eventually abolished it as beyond reform. There had been rumors locally for years that the Springfield Model Cities and CETA programs had been riddled with corruption and waste, and it was suspected that corruption might secretly be the primary reason why there appeared to be such nervousness in high places over what an in-depth audit might reveal.

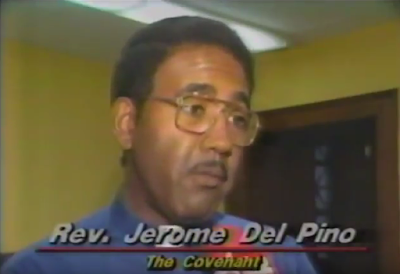

That nervousness was no doubt heightened when Mitch Ogulewicz did some investigative work on his own. Mitch discovered never before released audits of the Model Cities program, documents that revealed that over two million dollars was either improperly spent or was completely missing, with no idea of what it had been spent on or by whom. The Covenant was galvanized by Ogulewicz's revelations, with Covenant member Rev. Jerome King Del Pino declaring that Mitch's discoveries were "just the tip of the iceberg in what I assert was a comedy of errors to develop the Winchester Square locality over the past 20 years."

Yet despite the growing body of evidence of fiscal mismanagement, the Neal Administration became ever more insistent that no audit should be held. In a comment that took Mitch by surprise, Neal declared in a private meeting with Mitch and some other Councilors that "Some of those people who were involved in those programs are now upstanding citizens,who should be allowed get on with their lives."

A startled Mitch could only wonder what Neal meant by that statement. Who were these "upstanding citizens" placed in danger by the audit, and why should they be allowed to get away with past misdeeds? It seemed to Mitch that the Mayor knew more than he was willing to tell about the suspicions of the black community and the issues raised by the Covenant. Mitch thought it was also interesting that the scandal plagued CETA program had been administered during the Sullivan Administration, in which Neal himself had been an important figure.

In any case, Mayor Neal began applying pressure every way he could to defeat the proposal for the audit. Coming to his aid was Winchester Square's State Rep. Ray Jordan, who announced he would hold a special public meeting in which economic development in the Square would be discussed and all questions answered. The Covenant was unimpressed, accusing Jordan of offering to hold the forum merely as a substitute for doing the audit. They released a statement dismissing Jordan's rhetoric as "typical of his style during his 12 years in office." The Covenant turned out to have been correct in continuing to press their demands, because in the end it turned out that the tell-all public forum Jordan promised was never held.

On June 3, 1986, after weeks of intense lobbying by the Neal Administration, the struggle for the truth came to a climax when the Council voted 5-4 against funding the audit. The Covenant and most of the black community, along with other reform-minded citizens concerned with good government, were outraged. The Covenant refused to concede defeat, with Rev. Del Pino declaring in the Morning Union, "We are committed to the truth of what it is we are pursuing and we will not be deterred by any of the devious methods of avoidance that were utilized by each of the Councilors who voted in opposition to this proposal."

The Neal Administration was caught off-guard by the unexpectedly intense outpouring of public anger following the defeat of the audit proposal. It was obvious that the Covenant and its supporters in the community and on the Council were not going to let the matter drop. Finally Councilor Robert Markel came forward with a compromise proposal to fund an audit covering a much shorter period of time - 1979 to 1984.

This would remove from the investigation the time periods covering the Model Cities and CETA programs about which the Neal Administration seemed so nervous, and it would cost only $50,000, alleviating the concerns over the expense. The Covenant was not at all satisfied by this proposal, which essentially took off the table 75% of the time period they wanted investigated, but in light of the defeat of the larger audit they decided to accept the compromise as at least better than nothing. If this shorter audit showed the necessity for further inquiry, they could then return to the Council with their original, more in-depth proposal.

The Covenant insisted that a first rate auditing firm be charged with the investigation, and the respected company of Peat, Marwick, Mitchell and Company was chosen. At first everyone was pleased, but then some concerning things came to light.

To their shock and dismay, the Covenant discovered that the Neal Administration's Budget Director Henry Piechota had quietly changed the contract with Peat, Marwick and Mitchell so that they would perform an audit of all economic development in Springfield, with no special attention given to spending in Winchester Square. Such an audit would be so broad and unfocused that it would be uselessly vague, revealing nothing that wasn't already in the public record. The Covenant accused the Neal Administration of secretly trying to sabotage even this shortened audit. Rev. Del Pino condemned the Neal Administration in the harshest terms, "Mr. Mayor and Mr. Piechota," he cried out in the newspaper, "what are you trying to hide? This kind of bungling is no accident."

Mayor Neal promised to negotiate with the auditing firm to redirect their focus to Winchester Square, but the level of trust between the black community and the Neal Administration was by now badly frayed. Ogulewicz found himself being pushed into the position of the point man for the black leaders trying to monitor the audit, as he and Morris Jones were the only Councilors the black community seemed to trust. Even Morris Jones came under increasing criticism by The Covenant for what they described as his "hesitant leadership." Some complained that they felt that Jones was more concerned with his relationship with the white power structure than he was with the concerns of the Covenant and the black community. Therefore, it was increasingly Ogulewicz whom the black community turned to as the only person who had shown the courage to stand unwaveringly by the Covenant from the very beginning.

So the city waited for the auditors from Peat, Marwick and Mitchell to complete their work. And they waited, and they waited. Originally the audit was supposed to be ready in only 60 days. Then 90 days. Soon over six months had passed, with no results released or even scheduled to be released. Yet it was rumored throughout the city that the audit had in fact been completed and that the Neal Administration was sitting on it.

Finally, Ogulewicz decided that enough was enough. Calling a press conference on October 10, Ogulewicz demanded the immediate, unconditional release of the document. "This audit began in April." he said. "For $50,000 dollars we were told the audit would not take more than 60 to 90 days, and it is now six months since the audit began. All excuses for the final report not being released are not valid. Therefore I am calling for the release of the report immediately."

The Neal Administration initially refused Ogulewicz's demand, but under increasing public pressure the report was finally made public in December. The whole Valley waited with great anticipation for the results of this highly controversial document but found in the end that there was - Nothing. It wasn't that the audit showed that anything was wrong. It wasn't that everything was shown to be all right. There was simply - nothing.

It turned out that Peat, Marwick and Mitchell reported that they couldn't get the documents they needed from the Neal Administration or the Springfield Redevelopment Authority to have enough information to draw any conclusions about anything at all. Either the Neal people claimed the documents were lost or they turned over documents that were so sloppy and incomplete that the auditing firm simply couldn't gather enough information from them to make any definitive statements, except to say that the city's record keeping desperately needed to be improved. The Covenant was infuriated. "You have not yet begun to feel the wrath of The Covenant," cried the Rev. Warren Savage toward city leaders. The Rev. William Dwyer declared, "We feel that the audit shows a pattern of irresponsibility, particularly on behalf of the Springfield Redevelopment Authority."

But despite the outcry, the predictable spin doctoring soon began. Although the audit had resolved no suspicions one way or the other, Councilor Francis Keough stepped forward to declare that the audit had "lifted the cloud of suspicion" from all concerned. The Springfield Newspapers downplayed the missing documents and declared in its headline "Audit clears use of block-grant funds" although actually it had done no such thing. Despite repeated pleas from the Covenant not to let the matter drop, it became impossible to generate any more interest on the part of most Councilors toward any further investigation. The Covenant appeared to have been bamboozled off the stage of city politics, swept aside by Neal Administration rhetoric about "putting the past behind us and moving on." But the Neal Administration's victory over the black community was to be short lived, for no sooner was The Covenant shoved to the sidelines than another major controversy erupted in Winchester Square.

The Winchester Square clergy who made up the membership of The Covenant had been radicalized by their unsuccessful attempt to uncover what had become of the over 90 million dollars in economic development money that had supposedly been spent in the black community. The Covenant members had demanded that an audit be conducted to discover where all the money had disappeared to, but the Neal Administration, through a series of delays, deceptions and restrictions, had caused the final audit to be so vague and incomplete as to have been useless.

Many thought that their defeat would mean the end of The Covenant, but that was not the case. Having failed in their attempt to address the economic development boondoggles of the past, The Covenant then turned its attention to the economic development boondoggles of the present, in particular the $13 million dollar project to convert the former Indian Motocycle building into apartments.

The legendary Indian Motocycle Company had ceased manufacturing activities in Winchester Square in 1953. Its two large factory buildings remained partially in use throughout the 1950's and 60's, mostly through retail outlets on the ground floor, in particular the popular King's Department Store. In the 1970's however, the buildings became completely abandoned and soon fell into ever more serious states of disrepair. Ultimately, the larger of the two buildings was declared to be in such a state of structural weakness that there was a danger that it might simply topple over onto State Street, possibly resulting in injury or loss of life for any vehicle or pedestrian unlucky enough to be passing by when it fell. Therefore, in 1984 it was torn down by the city for the sake of public safety.

The smaller building, although also in tough shape, was becoming the subject of speculation for renovation as a housing project. Three prominent businessmen, Merwin Rubin, H. Joel Rahn and Jeffrey Sagalyn were trying to put together a proposal using taxpayer funds to renovate the building and redesign it for commercial use as an upscale condo complex. Not everyone, however, believed that to be the best use of the building or the site.

The members of The Covenant felt that what the poverty stricken Winchester Square community needed above all else was jobs. They wanted the building to be converted to cheap retail space where young entrepreneurs and small shops could be opened at rents that would help new businesses to blossom and to serve as an economic center for neighborhood revitalization. As for the plans to build condominiums, they sensibly asked just who was going to move into these condos right smack in the middle of Springfield's ghetto? From a purely business viewpoint, the whole concept behind the Indian Motocycle project seemed laughable. Furthermore, there was already more than ample housing in the neighborhood - if anything there was too much housing stock, with much of it abandoned. It was jobs and economic opportunity that the community needed, and the Indian Motocycle Apartments would provide neither. Yet, like so often in Springfield, it was not economics and common sense that would dictate the course of action - it was politics.

Concern over the political angle is what first brought Mitch Ogulewicz into the controversy. Mitch felt it was disgraceful how the Neal Administration had mistreated the clergymen in The Covenant during the audit controversy. It was obvious that the good old boys network had repeatedly failed the black community in Springfield, and Mitch was determined that in the future things would be different. Ogulewicz felt that both buildings should be razed in order to give the Square a fresh look and to create the widest possible range of opportunities for what the site could be used for. He agreed with The Covenant that the whole concept behind the condo complex was ridiculous. Who would want to live there? Why would any sane investor put their own money into such a sure loser? As Mitch tried to find out, he soon discovered that it was difficult to get answers.

When Ogulewicz was finally able to track down the investors and ask them how much of their own money they intended to risk in the venture, he was startled to be told that their investment would consist solely of their own "sweat equity." In other words, the time and energy they spent working on bringing the project into existence would represent their total investment. Mitch couldn't believe what he was hearing - the investors essentially wanted access to millions of dollars of taxpayer funds for doing nothing more than donating the effort they put into acquiring the taxpayer's money. Anyone at all could be a developer under those terms! Such an arrangement was unprecedented and seemed completely absurd from a fiscal perspective. What it really amounted to was just handing the building and the millions needed to develop it over to the businessmen as a gift.

Also acting as an "investor" in the scheme was the Upper State Street Community Development Corporation. Sitting on the board of this organization (later called The Mason Square Development Corporation) was none other than Springfield Newspapers publisher David Starr, who it turned out also had ties to Indian Motocycle Apartments developer H. Joel Rahn. Starr admitted to Valley Advocate reporter Stephanie Kraft that he had solicited Rahn in the past for some of Starr's pet charities. Kraft also reported that Rahn was a friend of Arnold Friedman, Starr's second in command at the newspapers, and that Friedman and Rahn had been seen dining together at area restaurants on several occasions.

Even more intriguing was that Upper State Street Community Development Corporation (a non-profit entity) had a for-profit subsidiary called simply "Upper State Street Indian Motocycle Building." Mitch was startled to realize who was the head of the money making operation tied to the project. It turned out to be none other than State Representative Ray Jordan, who was the politician representing the Square in the legislature in Boston, which was where most of the money for the project was supposed to originate from in the form of financing from the Massachusetts Housing Finance Agency.

So Mitch had uncovered this almost surreal situation where a historic building in Springfield's poorest neighborhood was being turned into condos that no one needed or were likely to buy, with investors who appeared to be putting little or no money of their own into the project, thereby leaving taxpayers to assume all the risks, while the publisher of the local newspaper, which was supposed to be a journalistic watchdog over the project, was sitting on the very board of the organization that the newspaper was supposed to oversee. Finally, the politician most responsible for the political and financial oversight of the taxpayer's investment, Ray Jordan, was himself the head of the profit taking subsidiary through which the investor's profits would flow.

On April 23, 1987, Mitch Ogulewicz held a press conference to demand that the State Ethics Commission launch a full investigation into the Indian Motocycle Apartment project and the players involved. On the same day, the members of The Covenant traveled to Boston for a private meeting with Governor Michael Dukakis, where they pleaded unsuccessfully with him to reconsider his support for the grants needed to begin the project. By this time, the black community itself had become torn over the project, with Ray Jordan putting together a group of his own supporters called The Winchester Square Coalition, which was formed to serve as a citizen counter group to the clergymen in The Covenant.

The Winchester Square Coalition held a press conference supporting the Indian Motocycle Apartments, and then released a statement accusing those who opposed the project of racism. An angry Ogulewicz immediately responded that the charge was a red herring, designed to draw attention away from the very real concerns about the project's viability and the ethical issues involved. Also accused of racism were City Councilors and project critics Vincent DiMonaco and Betty Montori, both of whom also responded angrily to the racism charges, especially Vinnie. When told by Winchester Square Coalition leader Ida Flynn that she would lie down in front of the bulldozers if necessary to save the apartment project, he bellowed, "If you lie down in front of that bulldozer, you won't be lying there long!" To which Flynn snapped back, "Nothing you would do would surprise me!"

Mitch felt concerned about the increasingly hostile tone of the debate, and regretted that the Winchester Square Coalition had introduced the race card into the discussion. Developer Merwin Rubin called for "cooler heads to prevail" before the bad feelings resulted in the whole project being scuttled. But the war of words raged on.

Mitch continued to demand an investigation, asking in the Springfield Republican, "How does Rep. Jordan justify his being involved with a for-profit subsidiary of his development corporation while attempting to secure taxpayer's money for his project? When I have asked about the equity provided, I have been told that the developer's equity is their time and sweat that they have put into the project. Where is the developer's money? How much of the money is from their own pocket compared to what they propose the taxpayers to put into the project? It is time for the Ethics Commission to look into the entire situation."

Jordan responded with strong words of his own, accusing Ogulewicz of "making a feeble attempt to make issues out of non-issues" and mockingly giving Mitch the nickname "Landslide Ogulewicz" because he was "always looking for votes." Jordan also ridiculed The Covenant for going to see Dukakis, saying that they, and especially Ogulewicz, had no influence with the Governor. When Mitch announced that he would try to call the Governor to give his side of the issue, Jordan sneered in the paper, "I'm sure that Gov. Michael Dukakis will be bubbling over in anticipation of receiving Mitch Ogulewicz's phone call."

Soon Mitch received some unexpected corroboration for his criticism of the Mason Square Development Corporation. Community Development Department employee James R. D'Amour wrote Mitch a scathing memo about what he saw as gross incompetence at the organization. D'Amour wrote, "Overall the agency, with respect to accountability is very disorganized. Files are lacking information and documentation. Reports are late. Staff doesn't seem to grasp necessary systems and procedures, even after many instructional meetings . . . same questions, same mistakes again and again."

Yet ultimately no appeal to reason, no logical argument, no concerns over economics or ethics - absolutely nothing it seemed could derail the project. Like some economic development Frankenstein, the project had a life of its own that kept it moving forward whatever the concerns of the Covenant, the black community, Ogulewicz, DiMonaco, Montori or the taxpayers. There were just too many well-connected people exerting too much influence in high places for the simple facts about how unethical and ill-conceived the project was to make any difference.

Shortly after the project was finally completed, it became obvious that the original prediction that people simply would not want to purchase condos in the ghetto was coming true. Almost immediately upon opening, the project went into a rapid decline, at one point attempting to survive by turning itself into a welfare motel that made income off of rents paid for by the taxpayers. But nothing could stop its downward spiral, until finally the whole condo project went crashing into bankruptcy court only a few short years after it opened. In the end, the taxpayers lost every single penny they had invested in it, exactly as The Covenant, Ogulewicz and the other critics had predicted. As for the politically connected developers, by that time they had already cashed their checks and moved on.

The total effect of the editorial and the paper's earlier charges was devastating. In a desperate attempt to save himself, Keough publicly attacked both Starr and Arnold Friedman, accusing them of secretly assisting the Jordan campaign and of engaging in conduct that “violates every canon of responsible journalism.” But it was too little, too late and on Election Day, Keough went down to a landslide defeat.

The total effect of the editorial and the paper's earlier charges was devastating. In a desperate attempt to save himself, Keough publicly attacked both Starr and Arnold Friedman, accusing them of secretly assisting the Jordan campaign and of engaging in conduct that “violates every canon of responsible journalism.” But it was too little, too late and on Election Day, Keough went down to a landslide defeat.